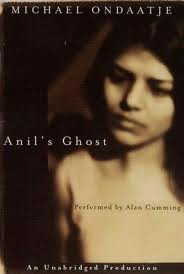

Nothing Civil About This War

This novel was published after the phenomenon that was THE ENGLISH PATIENT. It is more grounded in human tragedy than PATIENT, and hews more closely to the female protagonist’s (Anil’s) story than PATIENT’s Hana.

Ondaatje’s achievement here is capturing horrible truths in asides. It is in the actions of supporting characters that he makes his case for the best and worst aspects of the human experience.

In THE ENGLISH PATIENT, Kip the sapper lives and works at the edges of the novel’s principal plot. Yet it is in his seemingly incongruent actions that he is so effective a presence. For example, he hoists Hana on a line into the high shadows of the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo so that she can glimpse the centuries-old frescoes. In doing so, he lifts her above the nightmare of Nazi occupation in WW-II Italy and transports her across time to the heights of mankind’s artistic triumph.

In ANIL’S GHOST, we are dropped into the terror of Sri Lanka’s civil war. There she is caught between three intractable forces: leftist and separatist insurrections and the government’s ruthless repression. Here she collaborates with two brothers – one an archealogist and the other a doctor. In their world, abduction is to be expected, torture is a fact of life, and the aspirations of their professions – discovery, knowledge, compassion – are dark and threatening ideas. They are ultimately loyal to these values, these abstractions of light, shadow, and hope.

It is especially relevant reading now, when what appears to be nascient civil war threatens the Middle East from Tripoli to Tehran.

GHOST is deeply researched and written. It is a good addition to the literature of our time.

Related: Michael Ondaatje: Auteur, Author